Archaeology of the Green Sahara

Discovery and Excavation

In 2000 while prospecting for dinosaurs, a team led by Prof. Paul Sereno discovered an exceptional archaeological site called Gobero, preserving an unprecedented 5,000 years of habitation by peoples living in the latter part of the African Humid Period, from ~14,000-5,500 years ago. The site preserves an exceptional record of human burials, artifacts and fauna, providing the best window into life in the “Green Sahara,” a period of cultural diversification among lakeside inhabitants during the Early and Mid Holocene (~10,000 to 5,000 years ago).

Gobero was explored, sampled, mapped and excavated on six expeditions to Niger (2003, 2005, 2011, 2012, 2018, 2019), during which approximately 100 burials were excavated and more than 1,000 artifacts and key specimens of Gobero’s fauna and flora were collected. More than 100 radiometric dates anchor Gobero’s astounding record —some 5,000 years of near continuous occupation near shallow lakes rich in fish and attractive to wildlife (Sereno et al., 2008).

Gobero’s Central Mysteries

Most Saharan archaeological sites record a single short-lived occupation lasting decades or perhaps a century or two, before changing conditions force the inhabitants to move. No other site approaches the longevity of Gobero, some 5,000 years. That duration, that resiliency in the middle of the Earth’s greatest desert, ranks as one of it’s greatest mysteries. How and why?

The duration also gives rise to a second great mystery. At Gobero there are hundreds of burials, far more than any other site of comparable age, as well as thousands of artifacts and rock fragments from a very active stone tool industry. The site complex, then, was not just a longstanding cemetery but also a place of active habitation. Yet, only one disturbed burial has ever been excavated out of nearly 200. How is it possible to find burials-- sometimes in proximity and separated by thousands of years of time-- that are preserved as intact as the ancient day they were closed?

The answer to these mega-mysteries has taken years of field and laboratory research by scholars of many disciplines to unravel. Gobero’s ancient shallow lake, dubbed “Paleolake Gobero,” was supported by nearby groundwater gushers of freshwater, coming to the surface against a deep fault in the underlying dinosaur-age sandstones. Gobero’s steady water supply, thus, came from underground and was not dependent on rainfall.

The lake level at times flooded the gravesites and habitation areas, hardening and darkening the older skeletons, helping to preserve them. Longstanding lake levels, in turn, formed a hard rock in the root zone of reeds (called swamp ores) surrounding the occupied islands and peninsulas. This rock protected Gobero’s gravesites, otherwise buried in soft paleodune sand, through the millennia up to today.

Spectacular Burials

More than a dozen Gobero burials were excavated intact to provide a detailed record of skeletal position, grave goods and associated fauna. This was accomplished with a field jacket technique modified from that we use for older fossils in rock. Once prepared in the lab, the skeletons were CT-scanned to create a complete digital record of burials from predynsatic time. These digital files could then be segmented and animated to unfold the skeletons without disturbing a single bone. In that way, we could understand how the dead were positioned in the more complicated burials and calculate such metrics as stature.

Accordion Man

A well preserved burial 9,500 years old of a tall man, at 188 cm (6 ft 2 in), whose standing height was measured based on a CT scan of his bones. The hyperflexed burial position characterizes the oldest burials as Gobero. As none of his bones extend beyond a cylinder 25cm (10 in) in diameter, his body surely was bound at the time he was buried.

Turtle Man

A compact burial, presumably originally within an animal skin, that included a large carapace (upper shell) from a mud turtle placed under his pelvis. This is the only record at Gobero of this large mud turtle species, which survives today in muddy lake margins in Africa. At nearly 7,000 years of age, this burial is the oldest with grave goods at Gobero.

Bracelet Girl

A 10-year old girl, about 4,800 years old, buried wearing an ivory upper arm bracelet made from a large hippo incisor. Children have only rarely been discovered in burials with ornaments.

Halloween Man

An adult male some 7,000 years old with upper incisors filed to points and lower incisors removed. He holds the oldest record of tooth filing, a practice still present in Africa today, which, in life, would have given him a memorable smile. He was discovered on Halloween Day on the 2018 Expedition to Niger.

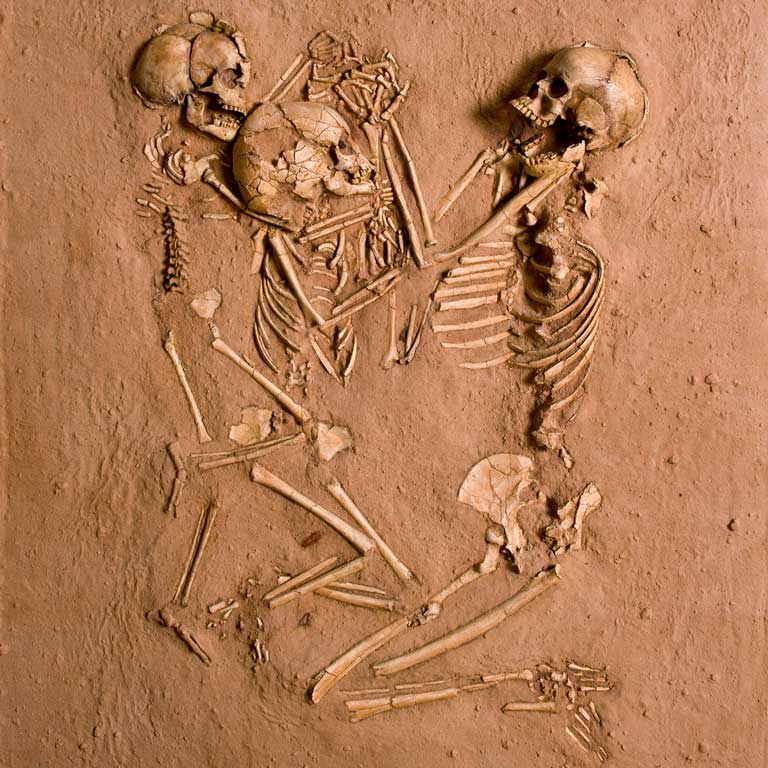

Stone Age Embrace

An adult female buried with two children, presumably her offspring, all holding hands, with four un-shot arrowheads as grave goods. This spectacular burial, the most posed in in prehistory from some 5,265 years ago, is presumed to be the result of an ancient drowning, as there was no indication of harm to the skeletons and no indication of stress prior to death in the molar teeth of the two juveniles, 5 and 8 years of age.

Beautiful Woman

A well preserved skeleton of an adult female, approximately 6,000 years old, in a side burial position with the pollen of a holly plant found under her head and pelvis. The holly plant grows only at high altitude and must have come more than 160km (100 miles) distance from the Aïr highlands.

Artifacts

Lithics are stone tools made of a variety of rock types at Gobero, the most interesting of which is a green and sometimes tan-colored igneous (previously molten) rock called felsite. In 2006 Paul Sereno and his team found ancient quarries of this rock type about 160km (100 miles) distant, on the eastern edge of the Aïr highlands. Some tools were made there and boulders of this source rock were transported to Gobero for tool-making on site. The most interesting tool type at Gobero is the “Tenerean disk,” a very thin circular or subcircular blade of unknown function only found in the central Sahara.

Barbed harpoons made of bone are common at Gobero, some found in place stuck in the now dry lake bottom sediments, where they lodged after missing prey many thousands of years ago. Made from crocodile and mammal bone, the harpoons turn black after centuries underwater.

Ornaments, or jewelry, made of bone and several rock types were found at Gobero. The most spectacular jewelry is a necklace, which was found in place in a burial of an elderly woman, composed of stone and ostrich eggshell beads with a central carved pendant made of hippo ivory. Other jewelry is made of a special blue rock called amazonite that was brought from rare outcrops in the Aïr highlands.

Fauna

Gobero’s vertebrate fauna included many mammals and reptiles as well as a frog, all of which are alive today in Africa. Larger species include:

- Elephant (Loxodonta africana)

- Hippo (Hippopotamus amphibius)

- Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis)

- Hartebeest (Acelaphus buselaphus)

- Warthog (Phacochoerus africanus)

- Crocodile (Crocodylus suchus)

Beaded necklace

Beaded necklace

Lithics

Lithics

Amazonite pendant

Amazonite pendant

Barbed harpoon

Barbed harpoon

Hook made of bone

Hook made of bone

Arrowhead

Arrowhead

Circular Tenerean disk

Circular Tenerean disk

Crocodile scute

Crocodile scute

Hippo tusk

Hippo tusk

Gazelle horns

Gazelle horns

Boar jaw

Boar jaw

Python skeleton

Python skeleton

Giraffe jaw

Giraffe jaw